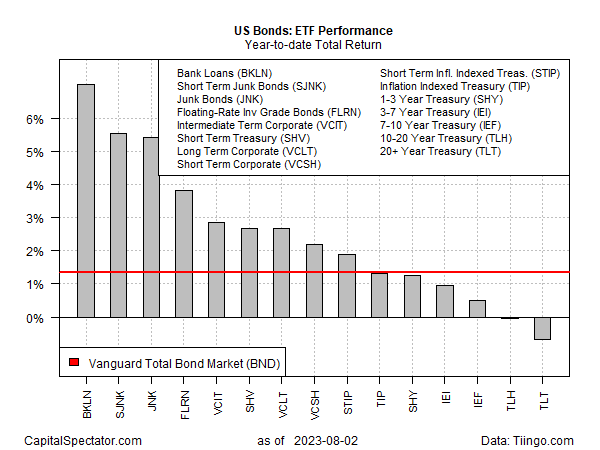

Interest rates continue climbing this year, but that hasn’t stopped bonds from rallying in 2023 when measured in total-return terms. The main exception: long-dated US Treasuries. Otherwise, the various slices of US fixed-income markets are posting year-to-date gains through Wednesday’s close (Aug. 2), based on a set of ETFs after adding distributions to price changes.

The big winners: bank loans and junk bonds. Invesco Senior Loan ETF (BKLN) is 2023’s top performer, climbing 7.0% year to date. Short-term (SJNK) and longer term (JNK) junk bonds are strong second- and third-place performers so far this year with 5.6% and 5.4% gains, respectively.

The downside outliers: long Treasuries. The iShares 10-20 Year Treasury Bond ETF (TLH) is currently slightly underwater in 2023 with a fractional loss while iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF (TLT) is down 0.7%.

Otherwise, bonds remain broadly higher. The investment-grade benchmark for US fixed income (BND) is up a modest 1.3% on a total return basis.

Readers may wonder how bonds can be posting gains in a year of ongoing increases in interest rates. The 2- and 10-year Treasury yields, for instance, started 2023 at 4.40% and 3.79%, respectively. As of yesterday’s trading, both are higher at 4.88% and 4.08%. Since yields and bond prices move inversely, there appears to be a mismatch. The explanation: fatter yield payouts have offset lower prices this year.

Consider the US bond benchmark (BND). In price-only terms, the ETF is down 0.4% for the year. After adding distributions to the calculation, it’s up 1.3%.

This week’s downgrade of US credit by Fitch throws a new risk factor into the market, particularly for Treasuries. Fitch Ratings cut the government’s long-term rating slightly to AA+ from AAA on Tuesday. The news rattled stock and bond markets, but JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon says “It doesn’t really matter that much,” reasoning that it’s the market, not rating agencies, that set borrowing costs.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen says the decision by Fitch is “puzzling” and “entirely unwarranted”.

Maybe, but the downgrade does highlight a significant fiscal challenge facing the US in the years ahead: debt as a percentage of the economy has increased recently and looks set to rise further, according to CBO. “Measured in relation to the size of the economy, deficits grow from 6.0 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) next year to 6.9 percent in 2033—well above their 50-year average of 3.6 percent of GDP.”

This isn’t a problem for the near term, but in time, perhaps sooner than expected, the red ink will start to impact fiscal decisions in Washington, one way or the other. But for the moment, the status quo prevails.

“There’s no imminent signs of Congress having the political will to address our entitlement programs or the revenue that funds them and the rest of the government,” says Shai Akabas, executive director of economic policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center. “It’s a sign of worse things to come if we don’t get our fiscal house in order.”

How is recession risk evolving? Monitor the outlook with a subscription to:

The US Business Cycle Risk Report