Jerome Powell emerged victorious in the political war that threatened to derail his re-nomination to lead the Federal Reserve for a second term. Winning the economic war that awaits, however, will likely be a much tougher battle.

In choosing Powell to head the Fed for another four-year term, President Biden “chose the status quo for monetary policy and financial regulation,” says Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics. “The Fed’s going to slowly but steadily take its foot off the monetary accelerator.”

The question that will come increasingly into sharper focus: Is the status quo up to the task that awaits?

The critical variable for answering intelligently is closely linked to how inflation evolves in the months ahead. Unfortunately, the future’s uncertain as ever. The fact that so many economists didn’t anticipate the recent surge should give everyone pause about assuming the future has suddenly become clearer on this front.

Uncertainty or not, the stakes are rising for making informed decisions on monetary policy. A careful review of central banking history reminds failure is always lurking. Think Jean-Claude Trichet at the European Central Bank a decade ago and his ill-informed decision to start tightening too early, which probably derailed the currency bloc’s nascent recovery. On the flip side, there’s the troubled tenure of Arthur Burns at the Fed’s helm in the 1970s, when he let inflation run amuck.

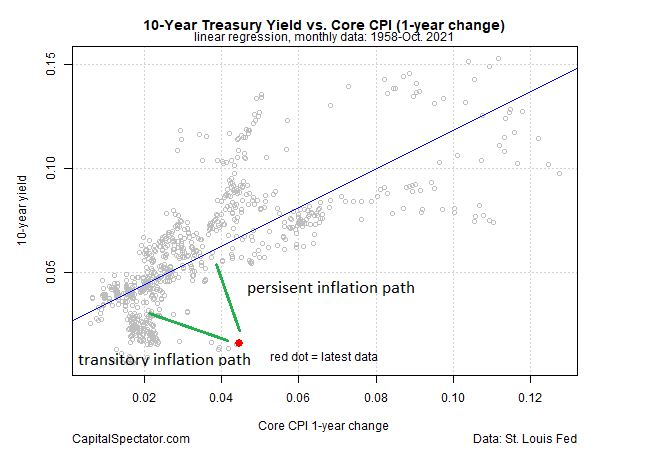

The challenge for today’s Fed is arguably the toughest in a generation, in part because it requires high confidence about where inflation’s headed in 2022. For a summary of the challenge, consider the chart below, which regresses core US consumer inflation against the 10-year Treasury yield since 1958. The red dot marks the last regression data point (Oct. 2021) with core inflation at 4.6% and the 10-year rate at 1.58%. (Note: the 10-year yield has moved up slightly in November, reaching 1.63% yesterday (Nov. 22)).

The current mix of yield and inflation suggests that the 10-year rate is well below a “normal” rate, given the history of the two time series. The question is how will the disequilibrium normalize? There are two paths. One is that inflation eases, fulfilling the forecast of some who say inflation is transitory. The alternative path: the 10-year rate will rise and adjust to the changing economic conditions unleashed by higher inflation.

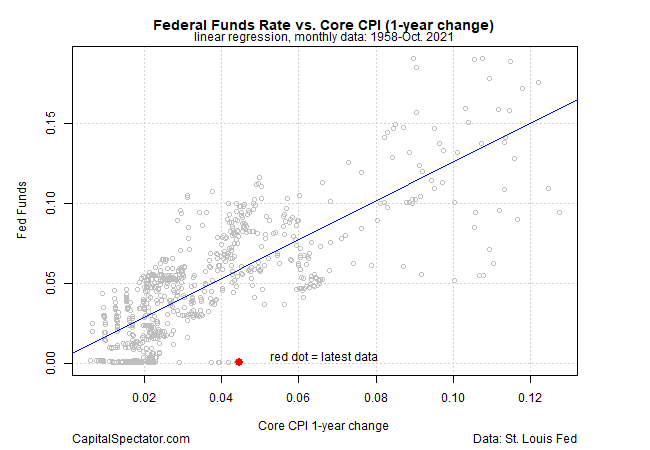

A similar profile emerges if we replace the 10-year yield with the Fed’s target rate, which remains pinned to a near-zero-percent level.

The Fed has signaled that it will only start raising interest rates after it’s finished tapering its bond-purchasing program. Depending on your forecast, that leaves a wide range of forecasts for when rate hikes could start: from early in 2022 to sometime in 2023.

Fed funds futures see the probability of a rate hike rising above 50% (just barely) starting in May 2022.

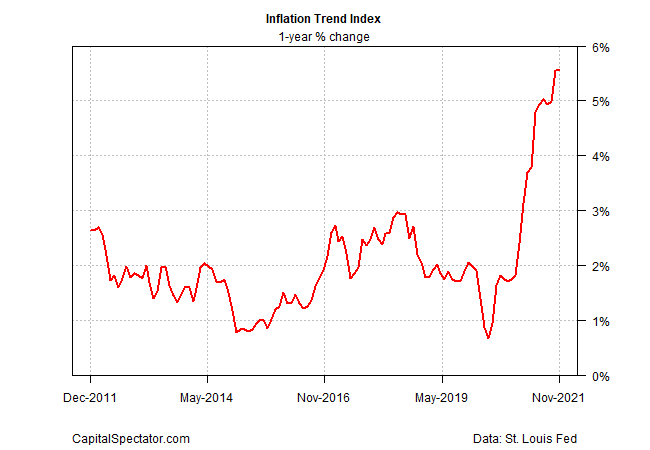

Meanwhile, all eyes are on incoming inflation data. For a naïve profile of how the inflation pressure is evolving for November, let’s turn to our Inflation Trend Index (ITI), which seeks to offer a degree of forward guidance on the directional bias of pricing activity in real time. Keep in mind that ITI is NOT a proxy for estimating the government’s consumer price index, which will be officially updated for November in a few weeks.

Meantime, ITI’s current profile suggests that this month’s pricing pressure is holding steady, albeit at an elevated level. Even if you’re inclined to agree, inflation appears unlikely to fade substantially in November. It seems that Mr. Powell has his work cut out for him as tries to navigate an increasingly risky path for monetary policy in the months ahead.

Learn To Use R For Portfolio Analysis

Quantitative Investment Portfolio Analytics In R:

An Introduction To R For Modeling Portfolio Risk and Return

By James Picerno

Pingback: Jerome Powell Wins Second Term for Federal Reserve - TradingGods.net