It will be gradual, with ample advance notice. And it’ll only begin once the economy has “fully recovered.” That, at least, is the plan for raising interest rates at some point in the future, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell explained late last month. The key question: Will the economy cooperate?

More specifically, will inflation remain sufficiently tame to permit Powell and company to slowly take away the monetary punch bowl?

“We are strongly committed to inflation that averages 2% over time,” the Fed chair says. “If it were to be higher or lower than that, then we’d use our tools to move inflation back to 2%.”

Fed Vice Chair Richard Clarida also outlined the current plan for gradual policy tightening, explaining that the central bank is intent on leaving rates unchanged until inflation’s running at 2%. “We are not going to lift off until we get inflation at 2% for a year. … We are trying to tie our hands. We are saying we are not going to hike until we get to 2%.”

Learn To Use R For Portfolio Analysis

Quantitative Investment Portfolio Analytics In R:

An Introduction To R For Modeling Portfolio Risk and Return

By James Picerno

By that standard, inflation hasn’t been a threat to the Fed’s gameplan. Core and headline inflation, based on the personal consumption expenditures, have been running at around 1.5% a year recently.

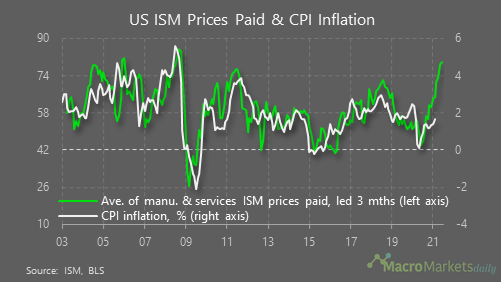

But with the economy heating up, and some measures of pricing pressure rebounding sharply, analysts are considering the possibility that inflation could reach 2%-plus sooner than expected. Notably, the prices paid data for US manufacturers has recently posted sharp increases that are far above the pace of consumer inflation.

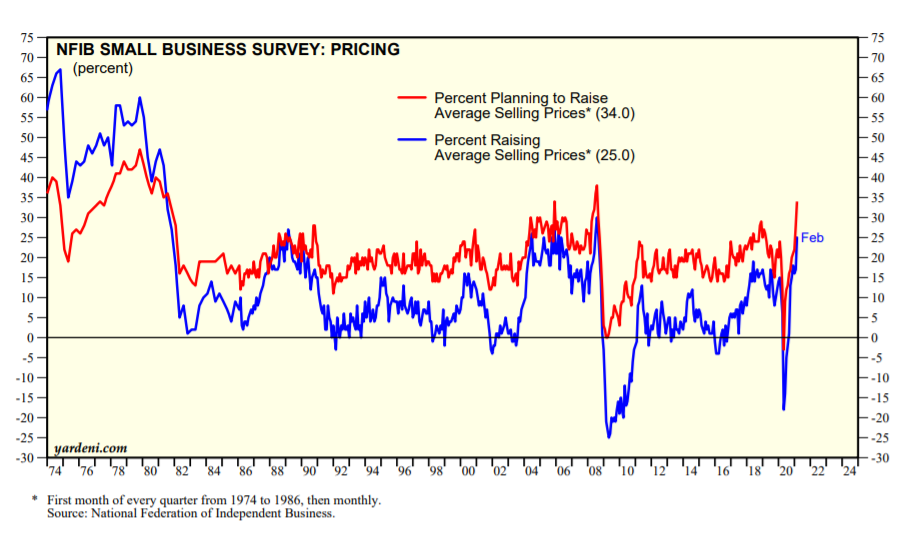

Also, recent survey data shows a dramatic rise in expectations among small business owners to raise prices.

A key factor that could change the calculus in favor of higher-than-expected inflation is the ramp-up in fiscal spending. Hot on the heels of the recently enacted $1.9 trillion stimulus and relief bill, the Biden administration is now pushing to pass a $2 trillion infrastructure spending plan.

“The bigger picture is that fiscal policy remains highly expansionary and is only one of several factors that point to a sustained rise in inflation,” advises Jonathan Peterson, an economist at Capital Economics, in a recent note to clients.

Grant Thornton chief economist Diane Swonk adds that the Fed hasn’t yet factored in the impact of infrastructure spending on the policy outlook, but investor sentiment has. “The Fed is not going to put that in their forecast until they see it, but the bond market is front-running that,” she says.

Indeed, the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield has climbed sharply in recent months and is currently at 1.73% vs. roughly the 0.5% level briefly touched last August.

Yet the market doesn’t appear to be pricing in rising odds of a rate hike for the near-term future. The 2-year Treasury yield, which is considered to be the most sensitive maturity for rate expectations, continues to hold in a tight range that’s prevailed for the past year.

Meanwhile, Fed funds futures are still pricing in low odds for a rate hike at the remaining five Fed policy meetings in 2021. There’s a modest uptick in the implied rate-hike probability for December – roughly 8%, but that contrasts with a near-zero estimate for the April and June meetings.

Incoming data, however, could alter expectations. The Fed is “going to go through the gauntlet now. They’re going to go through the toughest part of the gauntlet in April and May,” predicts Jim Caron, head of global macro strategy at Morgan Stanley Investment Management, “The data is going to be good. This quarter is going to test their credibility …The second quarter is going to be plus 10% growth and inflation is going to get to core PCE around 2.5%, and they’re going to say, ‘this is transitory.’”

Next week’s consumer inflation report for March will be a key test. But while headline inflation is on track to rise to 2.4% from 1.7% in February, core inflation will remain muted at 1.5%, based on the consensus forecast via TradingEconomics.com. In other words, the data will be sufficiently mixed to keep the debate bubbling about when the Fed will raise rates and by how much.

Even without a sharp ramp-up in economic growth it’s likely that inflation in the near term will revive as last year’s deflationary coronavirus shock fades in the year-over-year data. The question is whether there’s more than a one-time bounce that will lift and maintain pricing pressure beyond the next several months? The disinflation forces that have been in play are still relevant and so it’s not yet obvious that higher, permanent inflation is a high-probability forecast.

The challenge is that over the next several months it may be difficult to untangle the short-term bounce-back in inflation from any longer-term pricing pressures triggered by higher government spending, a rebounding economy and other factors.

For now, the Fed is confident that faster economic growth won’t force an earlier-than-expected liftoff in rates. At some point in the summer, after the initial inflation bounce-back is in the rear-view mirror, a clearer view will emerge of whether the Fed’s outlook is half-baked or correct. Meanwhile, expect a run of conflicting signals to muddy the waters. Perhaps that’ll be an excuse for the bond market to price in even higher rates as an insurance policy until it’s clear if the Fed’s gradual rate-hike policy is still viable.

How is recession risk evolving? Monitor the outlook with a subscription to:

The US Business Cycle Risk Report