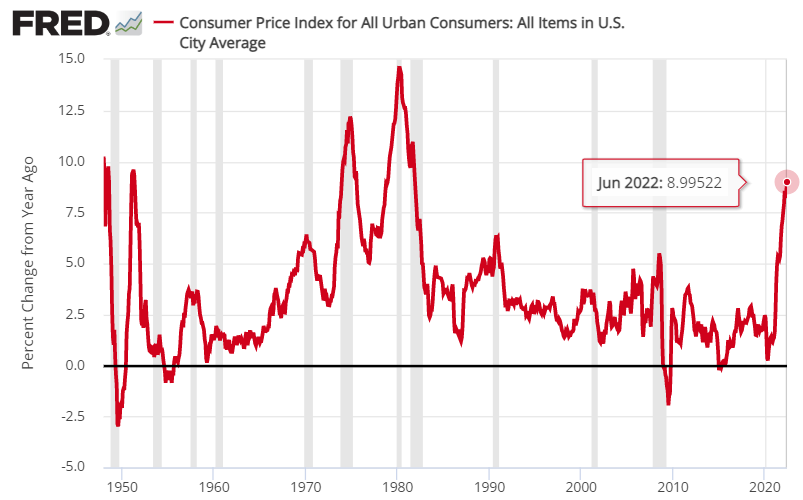

It’s all about high inflation at the moment. The Federal Reserve is certainly focused on inflation risk and is set to raise interest rates again in tomorrow’s policy announcement (Wed., July 27). The view that “inflation is transitory” is all but dead as a viable narrative on Wall Street and beyond and so the future looks obvious. Considering the potential for a return of disinflation/deflation (D/D) risk, in other words, appears clueless in the extreme. For that reason alone, let’s consider its likelihood at some point in the near future, if only as an exercise in contrarian thinking.

The main factor that may revive D/D is the elephant in the room at the moment: rising recession risk. History strongly suggests that whatever the prevailing level of inflation, the onset of recession tends to trim pricing pressure’s sails, sometimes dramatically. It could be different this time, but the economic record begs to differ.

A key reason that inflation’s trend tends to reverse during recessions: tighter monetary policy. The Fed remains on course to keep tightening, with another relatively hefty 75-basis-point increase expected (via Fed funds futures) for tomorrow’s policy announcement.

Analysts are debating how long the central bank will continue to raise rates, but the case for expecting a hawkish bias to persist rests on the view that the Fed’s inflation-management credentials are being tested and it can’t afford to fail. This line of reasoning says that nothing short of a clear reversal in inflation will suffice, which may take a series of rate hikes that last longer than expected.

A key focus on managing expectations is linked to tomorrow’s press conference with Chairman Jerome Powell. “He could talk about the [rate-hiking] cycle going well into next year,” says Michael Schumacher, Wells Fargo director of rates strategy. “The market is pricing a pretty quick end to the hiking cycle. That’s just not realistic. I think he’ll sound pretty hawkish.”

The longer the Fed tightens monetary policy, the higher the odds of recession and perhaps the deeper the pain and reversal of pricing pressure. Economist Nouriel Roubini says other factors suggest that an economic contraction could be deeper than anticipated by the consensus view.

“There are many reasons why we are going to have a severe recession and a severe debt and financial crisis,” says the chairman and chief executive officer of Roubini Macro Associates. “The idea that this is going to be short and shallow is totally delusional.”

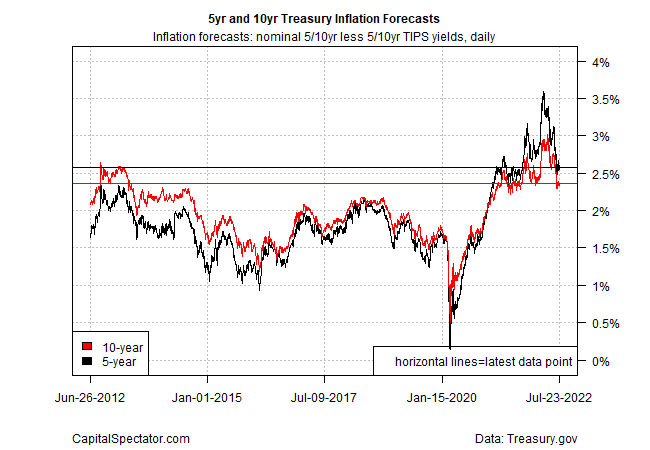

Even if a sharp recession strikes, it’s unclear how far and fast inflation would fall (assuming it falls at all). But uncertainty never stops investors from attempting to price in the morrow. At the moment, there are some hints that the market is considering that inflation will soon peak, if it hasn’t already. We’ve been here before, of course, only to learn that peak-inflation views were premature if not outright wrong. Nonetheless, the market seems to be reconsidering the possibility anew. If so, skeptics will say that the market is making the same mistake again. Maybe, but there’s no law that says that being wrong previously insures that you’ll be wrong the next time.

Meantime, the US Treasury market’s implied inflation forecast (based on the spread between nominal and inflation-indexed yields) has pulled back substantially recently, a sign that sentiment for peak inflation seems to be building.

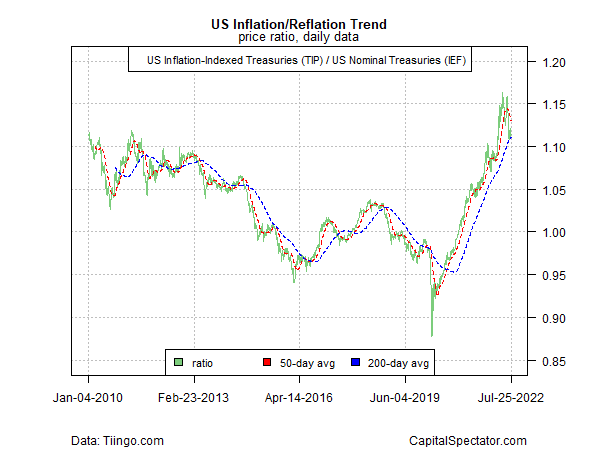

Consider, too, that a proxy for the reflation/inflation trade, based on the ratio for a set ETFs, may be starting to roll over.

Perhaps the bigger question is whether the forces that drove disinflation/deflation before the current inflation surge will revive as primary macro drivers in the months and years ahead? Aging demographics, rising use of technology that displaces workers and the so-called global savings gluts have been widely cited as contributors for the low-inflation era that ended (or appeared to end) last year.

The case for a return of disinflation/deflation is hardly open and shut, but the same can be said for assuming that high inflation will persist for years. We are, it seems, at a critical transition period that will determine what comes next. There are many ways to monitor this transition, but perhaps the best way is to start with Treasury yields. Not surprisingly, the market is less than decisive at the moment.

If and when the benchmark 10-year yield shows a stronger up or down trend we’ll have a clearer message on the outlook for inflation vs. disinflation/deflation risk from the crowd. Meantime, the jury’s out, although there’s a good case for expecting a verdict at some point in this year’s second half.

How is recession risk evolving? Monitor the outlook with a subscription to:

The US Business Cycle Risk Report